Turn Your OpenAPI Specifications into Executable Contracts — The Gory Details

19 Sep 2022

San Francisco, USA

Summary

Today, with the explosion of microservices and a plethora of protocols, ensuring in an automated manner that the API implementations actually adhere to their contracts is almost impossible. And on the other side, the consumers of these APIs have to hand-code the API stubs (poor man’s service virtualization), with no guarantee that the stubs actually adhere to their OpenAPI specifications. All of these gaps manifest as integration bugs late in the cycle. If these problems sound familiar, then this session is for you to understand how to leverage the very same OpenAPI specifications, so that they can be turned into contract tests and stubs without writing a single line of code.

As an author of an OpenAPI spec, you would like to ensure that the API developer who will implement this API is adhering to the contract. Learn how to author OpenAPI specs which can verify that the API is implemented correctly. As a consumer you often need to stub out your API dependencies while developing and testing your component. Learn how to set expectations that actually adhere to the contract, and thereby avoid late integration issues.

Transcript

Welcome everyone to this talk about API specifications as executable contracts. My name is Hari Krishnan, I’m a consultant and a coach. I advise both Unicorn startups and large enterprises on their transformation activities. These are some of the conferences I speak at, I volunteer at. I love contributing to the community and otherwise. My interest include high performance application architecture and distributed systems. So that’s quickly about me. Let’s jump right into the topic and I’d like to start off with a quick teaser or a demo of what I’m about to show you and then jump into the details of things. So this is an API specification conference. So what better way to start off than to look at some code, right? So here’s a fairly straightforward open API specification. It’s about an ecommerce app and it’s got a bunch of resources here, products and orders and crud operations on top of those two resources. And then I’m also claiming that I have this application, a springboard application that I’ve built out. And I’m claiming that this satisfies everything, all the operations as per the API specifications. Now how do we validate this?

What if I could take that API specification and run it as a test against my app and verify this is actually true? What I’m saying is true. So for that I’m going to be using this open source tool that we built called Specmatic. And I’m going to be trying to convert the API specifications into executable tests to start off with. So what I have here is a JSON file, it’s a config. And what I’m trying to do here is point it to a Git repository and also give it the location of the YAML file, which you just saw the open API file. And that’s pretty much all. And then I have this basic plumbing here which is going to say the coordinates for the application where it’s running localhost 80 80. And I’m going to say that’s pretty much all right. And this is extending Specmatic JUnit support. And let’s see what happens when I kick it off. So I’m using JUnit here, but Specmatic itself is platform and language agnostic. You could use it from command line and your application could be written in PHP or Ruby or Rustlang, it doesn’t matter. Okay, so the tests ran and overall there are twelve tests.

And where did these come from? So that’s the big question, right? So let’s analyze it one by one. Let’s take the first test. It says fetch product details. It’s got a method and it’s got a URL in there. Where did this come from? If you recollect the specification, the first operation here was Fetch product details and it was a get. So Specmatic practically took that open API operation and converted it into a test and ran it on my application. What do I mean by that? If you look at the log here, specmatic actually made a request out to say slash products ten. That number is of course random at the moment. And then when the response came back, it verified that the response is 200 and it also validated the schema according to the specification. So it looks like I’ve done a good job, right? I have written the code for the application and the app seems to be as per the specification. Well, that’s not very interesting, is it? It’s all happy parts and just twelve tests that got generated. Let me try throwing a curveball at it. So what I’m going to do is flip this switch called generative tests and I’m going to say Specmatic generative test is true.

And with that I’m going to kick it off again and let’s see what happens this time. So what I’m suggesting Specmatic to do now is to do boundary case testing, right? Not just test the happy path, do some boundary testing. Like what if I could send a string to a bully? And what happens? How does the application behave and whatnot? So if you notice earlier we had twelve tests and now we have 26. Where did the additional numbers come from? They’re right here.

So basically we have this test tagged as positive and negative. The positive scenarios are obviously the happy path. The negative scenarios are where we are playing around with the boundary conditions. So again, let’s analyze one of this test case. It says update product details. This operation failed. Let’s take a look at what happened. And it says 500.

That’s not good news. That’s definitely not good news. So what happened here? So Specmatic tried to send this request body and the ID is set to null. And what I know from this specification is the product cannot have the ID to be null. It’s a required and nonullable field. So if I send that, obviously the application should have handled a null, right? It should have done a null check and it should have given me a four to two or a 400, the appropriate error code, but it did not. So which is clearly indicative of the fact that there is a lacking validation and error handling in the application. So that’s good feedback, right? So this is what we call money for earnering and tests for free. So who doesn’t like free tests? So that’s like the quick teaser I want to start off with. And now let’s go into the actual content of the talk, right?

Going back to the content and presentation mode. So what I want to start off with is why this talk? Why am I doing this talk here? And why is it even relevant? What is it to the industry in the current situation that with all the widespread adoption of microservices, why is it important for us to adopt open API? Why is it important for us to adopt contract driven development? Those are all the questions buzzing in our head, right? And I’m trying to kind of first set up the stage and have a common vocabulary between us so that from then on we could look at the details. So let’s look into why the situation, right? So let’s say I’m building a mobile application and that requests product details from back end and then that service responds with the details and then displays it on the mobile app. It’s a fairly straightforward application, there’s nothing fancy here. So the mobile app which is requesting the data, let’s call it the consumer and the one responding with the data, that’s the provider. So just to set the terminology right now with that, let’s see how it go about building the consumer.

We could wait for the dependency, which is the provider, to become available in some environment. Then I can use that as a reference and then start building out my application. However, that might not be possible, right? Most of the times the provider might not be built or the provider is in an environment which is not accessible. I need to have to go onto a VPN and whatnot that’s very inconvenient. So what I would do as a mobile application developer is stand up a provider mock as an emulation of the provider, so that I can make independent progress on the consumer application development. This looks good on paper, but there’s a fundamental issue here which is the mock may not be truly representative of the actual provider. And why is this an issue? Because I could be wrongly assuming that I can send a string for the product ID while the actual service is expecting an integer and the service likewise could be responding with the name and the SKU of the product while I’m expecting the name of the price. So this means when we deploy both these applications in a common environment, we have broken integration and such issues.

What makes them worse is we cannot find them on the local environment like you saw already. And on the CI, the same story continues because you don’t have again, you have handrolled mocks or some custom mocking mechanism, right? For the provider it’s again the same issue because there is no emulation of the consumer for the provider. Even the provider is building out in its own isolated environment. The first instance where you realize such issues are happening is when you actually deploy them to something like an integration environment, right? And you put them together and then you realize there is a bug, it’s a compatibility issue. Now, this is a double whammy of an issue because number one, it compromises your integration testing environment, which means you cannot further test there until you really fix this issue or roll back. It blocks your path to production, which means you have unhappy users, right? The other issue is also the heat map here represents the cost of fixing such issues. The more to the right you find such issues, the more difficult it is.

The resolution. The MTTR for that is going to be much higher. So we want to be able to avoid this.

And this is a fairly straightforward situation. It’s just two components. The companies I work with have more like 100 to 500 microservices. And it’s not going to be easy. Even two microservices which are misbehaving can render your entire environment unusable.

So what we want to do is to be able to shift left the identification of compatibility issues, but not do it with integration testing, right. Basically kill integration tests and still have the ability to identify compatibility issues. So that’s the hypothetical ask that we have. How do we go about doing it? We are at an open API specification conference. We all agree that it’s a good thing to capture the communication protocol. And the schema that you are agreeing on should be put down in some sort of an open API specification or a WSDL specification. And then that could govern the building of how you are doing your consumer and provider application development. However, the fundamental question is just having the specification, is that sufficient? Not necessarily. Specifications in themselves do not form contracts, right. Specifications are there. They’re describing the communication between the two parties.

But in themselves they cannot be enforced. There has to be some sort of a development process which is baked in so that enforces the API specification. That makes it an executable contract. What do I mean by an executable contract? So that’s exactly what Specmatic is trying to do.

So Specmatic takes in open API specifications and for the consumer side, what it is able to do is stand up a mock server which is truly representative of the actual provider.

And why is it truly representative? Obviously it’s based off of the open API, right. It’s not just something that I hand rolled myself. Now I have to keep the equation balanced. So for the provider, I need to be able to run the specification as a test against the provider. So both these parties are being in lockstep.

Correct.

And that’s the teaser you saw a little earlier. Now this is the picture, what I wanted to paint in terms of what do I mean by executable specification, executable contracts? I mean, so if you have this sort of a setup, the consumer can independently build and deploy, the provider can independently build and deploy and you can be sure that they’re going to play well with each other, right. So let’s take a look at the consumer side story in a little bit more depth. The mocking side. So I’m going to do a live demo on smart mocks. And what do I mean by smart mocks? So let’s say I have this YAML file. Again, I’m going to look at a fairly straightforward, simple products YAML. I ask for products with an ID and I get back a response here with the name and the SKU. It’s just got one path, one operation, nothing fancy here. Now let’s say this is the YAML you all have given me and I am the mobile app developer and I need to set up. I can get started with my mobile app development. How do I go about doing it?

So first step I might do is I import it into postman. I have got it here and I’d like to try it out right, like play around with it. But then I don’t have a server to play with. So what do I do? I can stub it. So essentially what I can do here is Specimet. Oh, I’m so sorry. Thanks for that. I’ll repeat this part. So I have this specification file, which is just one path and one operation here. And I can give it an ID and I’ll get back the details of the product. That’s pretty much what the specification file is. Now what I’m trying to do is I have imported it into postman and I can try sending the request. But yeah, I don’t have a server for reference, right. So what I’m going to do now is ask Specmatic to stub it out for me. So Specmatic stub and I’m going to give it the Products YAML.

And it says it’s running in port thousand port 9000.

So let me try this out now and I get back a response. Now obviously this is a random response. Every time I send it, I get back a different value. That’s not very useful. If I’m trying to build an app, I want something specific, right? For example, let’s say if I give it one, I want this book details called Mythical Man Month and I want the SKU for that. Now how did this happen? Every other number was giving a random response, but one is giving me a specific response. Right now that’s happening because I set up this expectation data. This folder called Products underscore Data is based off of the naming convention for Products YAML. Under that I can add as many JSON as I can and each JSON is a request response pair. So here I’m saying that for the request with URL and ID one, I want to return Methical Man Month and this SKU. That’s how it’s working. Now this is still not a smart mock. What really makes it a smart mock is the next step, right? Now earlier you saw I was making this wrong assumption that this guy is going to return me the name and the price and not the SKU.

So let’s try doing that. I’m going to kill this and say this guy is going to return name and price and see what happens. You see this error here? So Specmatic tried to load the stub file and it said key name price in the stub was not part of the contract. So even if I wanted to add a wrong expectation data, I cannot. It has to comply with the specification. And that’s what I mean by smart marks. So what this means is if the specification evolves and if I am left with stale stub data, I cannot be allowed to do that. This will catch me and give me immediate feedback there. So that’s what I call smart mocks. What we can do further here is this guy, right? It’s not always possible to say, I can always think of what ID has to give, what response. That’s static mocking, right. What if I have a workflow test? Like I have one test and then the next test and the next test, and the result of the first test is something that is the input for the second test. How do I tackle that? The scenario like this, right?

So in this case, I need to be able to dynamically set up an expectation with Specmatic. And how I do that this time I’ll make sure I escape from the presentation. So you can see this.

So Specmatic also has this URL called Underscore Specmatic expectations. So what I can do is send the expectation the same JSON content which you saw. I can post it out to Specmatic over Http and it’ll do the same validation that you saw against the specification and still give me feedback. It’ll tell me 200 if it’s going to accept and if it’s not according to specification, it’ll spit it out saying it’s a 400 bad request. So I have feedback there, right? So that’s what I wanted to cover in terms of what is smart mocking. Okay, so how does this all come together right in the context of a test? So let’s look at the anatomy of a component test in general. What is a component test?

A component test is something a good component test always isolates the component from its dependency so you are able to verify the component in itself.

So how does this look? Any test has three parts. The test itself, the system under test, and then the dependency. In this case, you’re isolating the dependency with Specmatic. It’s basically mocking it out. And within the test there are three stages arrange, act, assert. So the arrange phase is where you would set the expectation with Specmatic. And as you saw, Specmatic would verify it against the specification and only then keep it into the storage. And then you do the act. So which means you call the feature you want to test. And that in turn makes the system under test invoke Specmatic and then the journey back and then you assert. So this is the overall picture, right. So this is what I wanted to quickly show you what I mean by anatomy of a component test. Now this in real world would look something like this. I have this karate API test here. I’m not sure if this is big enough. I hope you can read it. So there is the arrange phase here. Here in the arrange setup. I’m actually calling Specmatic on the expectations URL. I’m sending it the stub data or the expectations data, making sure that Specmatic accepted it.

So it’s a 200 and not a 400. And once that is done, then I actually invoke the API that I really want to test. Right, the system under test and that’s what the localhost 80 80 here is. And then comes the assert phase. So essentially you could use this setup with any testing framework, right? I’ve done this with Karma, with angular for the UI. And here I’m showing you for API testing with karate. So that’s about the consumer side. Now let’s switch gears and look at the provider side. Now the provider side is interesting, and you already seen this part. Basically, if you have the specification and you have the provider, all you need is the test, right? And we could generate it and fire it off at the provider. But what I want to show you is something a little bit more interesting, right? You already saw how you can generate tests. But what if I have a situation here where I don’t have an application? It’s a blank slate. It’s just Kotlin directly created out of Springboard Starter. Nothing here. What I also have is an API specification, which you are all too familiar with for products.

And that’s pretty much all. So if I have free tests and no code, what can I do? I can run the test first and then write the code. Can I do test driven development here? I could potentially. Right, so let’s try that. So I’m going to run this and obviously it’s not going to pass. But what’s important is what’s the failure? And then how is it guiding us in order to fill in the blanks, right? So notice how we really did not generate any scaffolding or anything. We’re using the test as a guidance to build out our code. So test failed as we anticipated. What is the issue? It’s a 404, obviously, because there is no path to support it. So what I’m going to do is quickly take the Snippet here and paste it in. I’m going to say there’s a get mapping for this particular controller. And like any good developer, I’m just going to return hello world. Why not let’s just do that and see if we lose the 404 and move forward. Baby steps, right? I’m a big fan of Kent Beck and his work. So I usually try to do TDD even in my regular scope of work.

So when I have something like this, why not play around with it with TDD? So let’s look at what happened now. And this time it’s a 200. Okay, it’s not a 404. But then obviously Specmatic verified that the response is hello world. But the specification says I’m supposed to get back an object with name and SKU and you did not write the proper code, so that’s good feedback. So let’s go ahead and do that. I’m going to paste that in also. So I’m going to put in a data class very quickly into this file. Sorry, wrong file. And I’m also going to return a book so that this guy is happy about the response.

So I’m going to kick it off. Let’s see if it’ll pass. Do you think it’s going to pass?

No. Okay.

Sorry. Yeah, that’s an interesting question because right now what happened, if you look at the test results, is this guy received a random ID, right? 382. I did not pass an ID. That’s a good point. So Specmatic generated some random number and sent it. But I have hard coded to return the same book every single time. So the test passed. So we are in the green. So we went from red to green. So I’m going to fix the problem that you asked about, right? So usually we’re not going to have test data for the entire gamut of random numbers. So I’m going to emulate it by saying if the ID product ID is not equal to two, let’s say that’s the only product I have. I’m going to throw runtime exception.

What’s going to happen now? Obviously it’s going to fail, but we don’t know what it’s going to fail with. So it’s always a good interactive session with your IDE to write a test and see what it fails and what’s going on. So let’s see what happened.

Wow. There’s a null.

And 500. Oh my, that’s not good. That’s definitely not good news. So what I need to tell Specmatic now is don’t send a random number. I need to send two. How do I do that? So let me go to the YAML file, and for this, I’m going to leverage the examples right in OpenAPI. So I’m going to put in there’s an example here for 200.

Value is two under the ID. Now I’m also going to put examples here on the response side just to balance it out that I’m expecting this book in response. So I’ll run that. Let’s see if that test passes now. Any guesses? Red, green, hooray green. What I want to call your attention to here is I did a subtle naming convention thing, right? I did 200 okay here for the example name, and I also did a 200 okay here for the example name in the request and the response, because Open API does not have a connection between the request and the response. I could have one request, then I could have multiple response codes. And for each response code, how do I even say this is linked to this, right? That’s where Specmatic has this ability to glean out of this. So if you follow the naming convention that this is the example and this is the response example somehow connects that and it’s able to figure it out. So what this means is now I could potentially go on to do fancy stuff like I can say for four or four, I can add one more example here and say for value zero, you have to look for an error response which looks something like this.

And notice how suddenly my whole coding style has changed, right? I am not starting to write the code first. I am beginning by writing the specification. Isn’t that significant? Because now suddenly the specification is almost indifferentiable from a test. I’m literally writing the specification and then my code. I’m trying to fill up the blanks, which means my code is always going to be built to spec. It’s not going to exceed, it’s not going to be less than. It just enough. So that’s the quick demo I wanted to show. We call it the Traceable approach. If you’re familiar with acceptance, test driven development, to me, for an API, the open API, spec is the acceptance criteria. It’s one of the definitions of done.

So that’s what I wanted to demonstrate here. Okay, so let’s quickly switch gears and move forward. So you saw provider side story. You have the consumer side story. What about the contract itself? What about the contract story? Compatibility issues don’t happen on day one. It’s very difficult, right. You have to try hard and have to be really wanting to make it happen. It’s with evolution. That’s where the problem is, right? You want to add features and that’s when you realize that in order to support consumer two, you may break compatibility with your existing consumer one. Now, how do we figure things out here? So I want to quickly show you a live demo of contract versus contract. Or how do we check backward breaking changes?

I’ll start out with a pop quiz, a very simple question. Which of these changes are backward compatible in a request? If I add a mandatory or a required field, is this a backward compatible change?

Very straightforward, right? Why take our word for it? Let me actually try figuring it out with specmatic. So under this folder I have two files, products V one, YAML, which is a post for creating a product. And my bad, I’m so sorry. So here I have two files. Products V one, YAML has an endpoint to create a product with post. And V Two is the exact identical replica of the same.

So what I’m going to do is try and compare these two. So I’m going to say Specmatic compare products V one with products V two. Now obviously, this has to return that they are compatible, right? Because exactly identical files. But what I’m going to do now is in V two, I’m going to make the change that we just saw in the example. So instead of adding a new property just because I’m lazy, I’m going to add make the SKU itself mandatory. It’s not mandatory now, but I’m going to make it mandatory. And after that, I again run the same command says new contract expects SKU in the request but the earlier one did not. So it’s backward incompatible. So at least we have a true test, right? What we guessed in our mind, the tool is also doing the same. So we have some sort of trust with the tool now. So I’ll undo that, go back to our original scratch which is compatible stage. And then I’m going to ask you the second question in the request. If I change an optional nullable field to optional non nullable, not compatible. Compatible. Well, let’s find out.

What I can do is here’s SKU it’s optional already. It’s not nullable though. I mean, it is nullable. I’m going to make it non nullable. That’s what the quiz was about, right? And I’m doing that change in V two and I’m going to run the compare again, see how it figured out that now we are expecting a string, but earlier it was nullable.

This is slightly more complicated than adding a mandatory field, but it’s still mentally easy to process, right? But what becomes harder with time as I’ve been working with large number of open API contracts. What if I had a schema component that is referenced both in the request and the response and add to it if it is at various levels of hierarchy and further add complexity if I have remote references, becomes impossible to compute in the mind. Let me show you an example of one such contract here. So this specification is not very significantly difficult, right? It’s an ecommerce inventory and order and storage management system. But what is critical here is there is this component called address at the very bottom. And the problem here is if I search for where the address is being used.

Typo okay, I have it being used in the warehouse and storage which is part of the request and it’s also used in the response here in the cart response. Now, if I’m a new engineer on this team and you task me with the activity of making street optional, I am completely clueless. I don’t know if I’m going to break backward compatibility. That’s where it’s useful to have automation around it to figure out which is a backward breaking change and which is not.

Again, right now it could be based on simple rules, but you will also need heuristics to figure this out so that’s quickly about the contract side of the story. So now, again, switching gears, moving forward, we saw three things now. Contract as test, contract as stub, contract versus contract. The fourth thing I want to talk about is something called central contract repo. And I’m going to be talking about why we need to start treating open API as code, like treat your contract as code. And this question are we on the same page? Why does this matter? With all this hard work we have done so far, I could still. Go for. As a provider engineer I could make a small little change to the provider and then forget to update the contract. And as a consumer engineer I forget to pick up the latest version. Maybe someone sent it to me on mail, I forgot to look at it or I forgot to pull the latest one. Right, so which means we are back to square one. That’s not a pretty place to be, right? That doesn’t make sense. What we want to do is have a single source of truth for our open API specifications, which is where we try to maintain them in a git repository which we call the central contract repo.

Again, it could be any version control system for that matter. Now, if you’re doing that, you might as well have a pull request or a merge request process. Which means in that process you could incorporate a lender for basic verification of your contract and then the almost critical backward compatibility verification. And for that, you know how Specmatic does that? Just like I compact two files, you can also compare two SHA’s in a git log, right? And once you’re done with that, you could do a review and a merge phase. Of course I recommend having as much automation as possible and not have manual review as much as possible. But then this would be your central contract repo process. And why is this useful? Sorry, I missed one point. So if at all it’s not compatible, what do we do here? If it’s not compatible? That under build pipeline. The pull request is not allowing to go forward. What we could do is do versioning, right? So what we do is a fairly straightforward semantic versioning but then it’s up to individual teams as to what they want to do. Semantic versioning that we follow is if it’s a backward incompatible change, we do a major version bump.

It’s a backward compatible change, we do a minor version bump. And if it’s just a structural change, if I’m extracting a common schema out, then we do just a patch. So that’s what we’ve been following and it’s working out fairly well for us. Now, once you have it in the central git repository, it means for the consumer and the provider they can pull it from that central repository. You remember the Specmatic JSON config I have from my teaser? That’s how you pull it.

So basically, Specmatic is always pulling the latest contract from the central repo which means be it your local laptop or be it your CI, you’re always working off of the proper source of truth from git. So with this, all four components need to come together, right? Contractor test, contractor stub, backward compatibility and the central repo. How do you embrace CDD? So, you know, Specmatic can pull your specification from the central repo which means it can make it available as a contractor stub for your consumer contractors test for your provider and that’s from the local environment.

What happens in the CI for the consumer once you finish your unit testing? You don’t have to look for another tool for the component testing, right. For Stubbing out your provider, you could use the same contract as Stub, which Specmatic gave you on your local environment because it’s just an executable.

It can run in any environment. And likewise for the provider, after the unit tests are run, we always recommend running the contract test first and then the component test. Why? Because a contract test is going to verify the signature first, make sure your API is in line with the Spec before you verify the logic with your component testing.

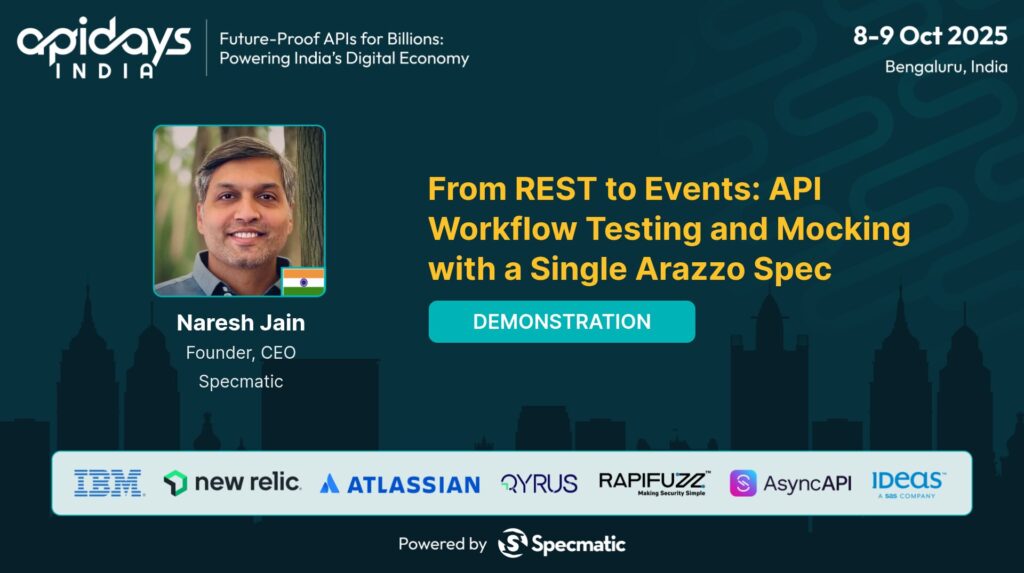

It kind of saves you one extra step. Now, since you’ve been adhering to the specification both on your local and on the CI for both the consumer and the provider, when you deploy it to its environment, such as integration, you can be pretty sure it works, right? Which means you have a viable environment for workflow testing and that means you have an unblocked path to production. And with regard to the heat map, that was the initial ask, right? Can we shift left the identification of compatibility issues and avoid integration testing altogether? And that’s what we’ve been able to do with Specmatic. Now by leveraging the API specification as an executable contract, which means for each microservice you can develop and deploy independently. In my mind, that’s the asset test for whether you’re doing microservices right. Can you deploy a single microservice without having to wait to integration test with all the other pieces? Of course, workflow testing is still important, but what this helps with is make keeping that environment for workflow testing still viable, right, and not be plagued by silly compatible issues. Compatibility issues. So yeah, with that I’d like to show some credits and that’s our team, Narish, Joel and I are the ones who are working on Specmatic and we are also very thankful to the contributors in the community.

And of course, we are very grateful to our early adopters in the industry who’ve been able to pick up this tool, run it in their real systems and be able to give us feedback based on which we’ve been able to evolve the tool and also our understanding of contract driven development. And with that, I’ll open up for Q & A. Any questions?

If it’s compatible, it’s not going to tell you anything, right? It’s still compatible if it’s yeah, I mean, if you really wanted to log it, you can make it verbose and it will tell you there is a change, but it’s a compatible change. Any other questions? I’d be happy to chat about it. I’ll be around in the lobby and stuff and yeah, thank you very much. These are my social handles across the board. LinkedIn, Twitter, wherever you can find me. Hari Krishnan, 83, and I do encourage you to check out Specmatic. It’s open source, so feel free to give us feedback and we’d be more than happy to hear from you in terms of GitHub issues, or if you’d like to contribute, or even if you think we are doing something wrong. We’re all ears to figure out if there is something which we need to improve upon. So, yeah, thank you again.